In this final post of our series on visual style, we’re going to follow our deep dive into cinematography and mise-en-scène with a look at montage. No, not that kind of montage. This kind of montage.

What is montage?

It’d be easy to say that montage = editing, but that’s not entirely true. Montage flows out of film editing techniques, sure. Editing, at the risk of over-explaining, is the selection and joining of various sequences of filmed action. Montage is editing, absolutely, but it goes a little further than that: montage is how we use editing to make meaning.

To really dig into this, we’re going to have to sidetrack slightly and spend a bit of time talking about film form and classical Hollywood style. Buckle up.

Film Form

“Form” denotes a recognisable pattern and structure to a piece of art – any artistic medium, not just film. This allows us to understand the artwork, to know how to make sense of it, and to know how to fill in the bits that it can’t provide for us because of various restrictions around that particular medium.

If you’re listening to a piece of music, part of your enjoyment (or otherwise) of the music is going to come from your own expectations of melody progression. If you’re reading a novel, you’ll come to it with a certain understanding of how novels work, and that will allow you to do the work of making sense of the narrative, of understanding the characters, of picturing the settings, of following the story structure. Part of that will be shaped by the narrative expectations set up by genre, but that’s a whole other kettle of aquatic lifeforms. For now, you can think of form as a kind of unifying structure that prompts us to understand an artwork in a certain way.

So, for example, if we look at The Matrix (1999)…

What do you mean, “get some more recent cultural references?” 1999 was, at most, five years ago. How very dare you.

Anyway. Like all films – like all works of art – The Matrix is comprised of a system of elements. In a film, the elements are things like the narrative: to whit, Neo living his ordinary life and feeling as though there’s something missing, followed by the arrival of Morpheus and his escape from the matrix, followed by his training and his slow induction into his new reality, followed by have the establishment of the rules of this new story universe. And so on.

We also have a very specific set of stylistic elements in the film too: there’s the bullet time feature, for one (every single action film of the following decade salutes you, The Matrix); there’s the washed out colour scheme that denotes the “real world” versus the saturated colour scheme of the world of the matrix. We have elements that are drawn from martial arts films and we have elements that are drawn from action films and we have elements that are drawn from sci-fi films. We have musical cues that help us muster the correct emotional response to various plot developments. All of these elements function as a system and we, as the viewer, because we have an understanding of film’s form, understand that they function together and we relate them to each other.

And we use these elements to make sense of other elements within the film. For example, we’re primed to accept a fast-paced soundtrack as a cue to understand that this is an action sequence; we can recognise an approaching scare; we can recognise a love theme as denoting a romantic episode… and so on.

Form shapes our expectations. As an example, let’s take one element of film form: narrative. Because we intrinsically understand how narrative functions (and again, this isn’t innate – this has to be learnt), we understand that events unfolding in a film are going to be related to each other. Say the CinePunked team are out and about and Robert drops a copy of his very reasonably priced book on The Wicker Man. You happen to be walking behind us on the street and you bump into Rachael as she stops to pick it up. What’s happened?

Well… yeah. You’ve just bumped into Rachael as she stops to pick up a copy of Robert’s very reasonably priced book on The Wicker Man. We all probably exchange rueful grins, mutter some apologies, and that’s that. We all go our merry ways, and probably you’re inspired to go to our website and purchase a copy of Robert’s very reasonably priced book on The Wicker Man, but that’s the extent of the incident’s repercussions.

But if we happen to find ourselves in a narrative, structured by formal expectations, and Robert drops his copy of The Willing Fool, Rachael stops to pick it up and you bump into her… suddenly, it’s not just a thing that happens, but it’s a thing that happens as part of a narrative, and it’s going to throw up expectations. Narratives are structured around causality: one thing happens and it causes another thing to happen, and so on until Randy Quaid’s flying a fighter plane into the energy beam of the invading alien spacecraft. (No, really, Independence Day is definitely no more than six, seven years old. Tops.)

Basically, a narrative is a chain of events in a cause-effect relationship. The famous example is this: if we said to you, “The king died and then the queen died,” that’s not a narrative. There’s no causal connection to the two events. But if we said to you, “The king died and then the queen died of grief,” that’s a narrative, because the chain of events is causally connected. And when you’re engaging with an artistic medium structured around a formal element that tends to invest heavily in causal connection (that would be film, in case you’d forgotten what website you were on), anything that happens within the confines of that medium prompts you to expect that the next thing that happens will be in some way causally connected.

What that next thing will be – and your expectations of what that next thing might be – will be structured by other formal elements, particularly visual style. (Music and genre also play a big part here, but bear with us on the visual style thing, or we’ll be here all day.) So, say Rachael stands up, The Willing Fool in hand, and the lighting and camera focus suddenly do this:

…well, the viewer immediately recognises that the causal connections that follow will be shaped to a large extent by the expectations of a romantic narrative.

Equally, if she stands up and the lighting does this:

…bad news, my friend: you’ve got yourself embroiled in a hard-boiled gangster narrative and it doesn’t end well for you.

Finally, if she stands up and we suddenly cut to a high-angle Extreme Long Shot with you, Rachael and Robert framed from two storeys above, we understand that the kerfuffle is being watched from afar, likely surreptitiously, and you’ve just joined the ranks of an espionage thriller.

There’s a fun little game you can play, should you want to explore how film form contributes to your understanding of cause and effect and your expectations thereof – you’ll find it in Film Art: An Introduction (David Bordwell & Kristen Thompson, 1997), but we’ll paraphrase here with all credit to its authors.

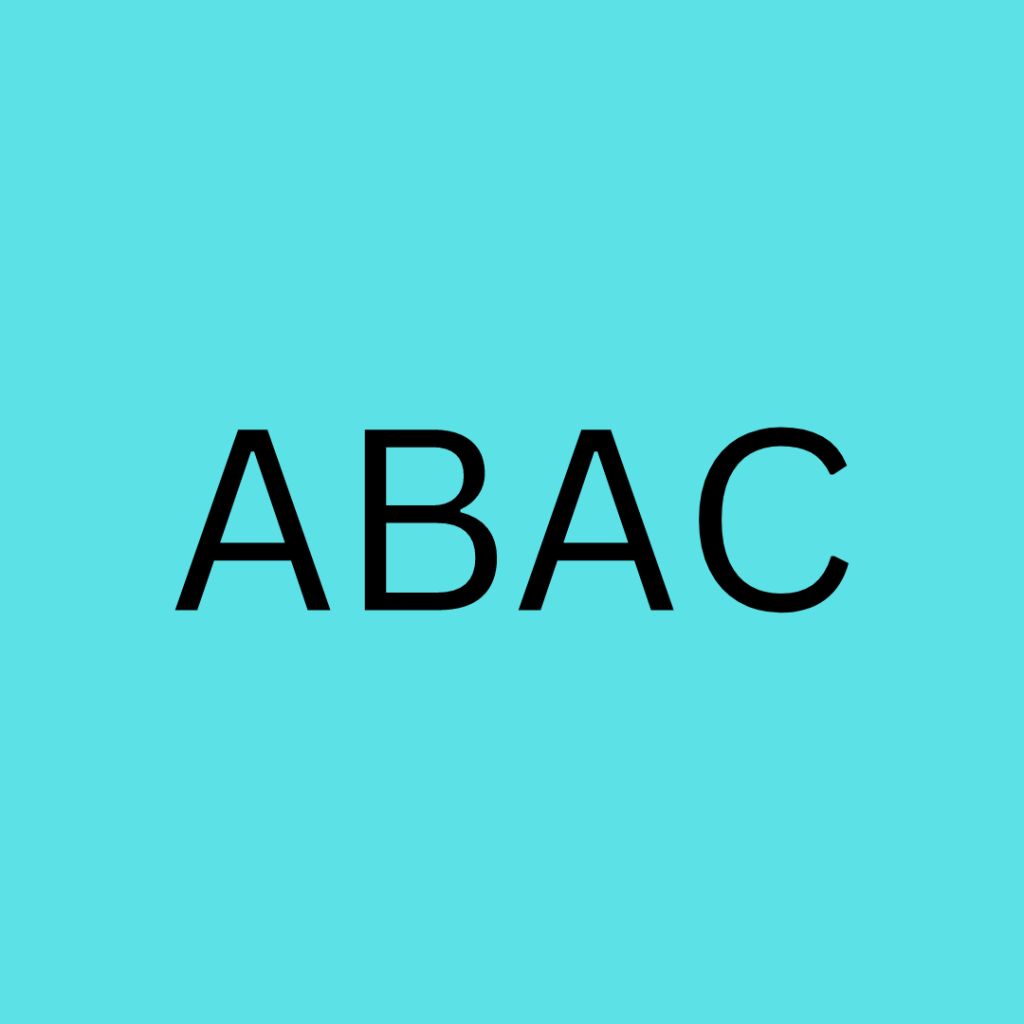

We present: Exhibit A. Literally.

This letter is the first in a sequence. If we were to ask you what comes next, you’d probably guess:

And you’d be quite correct. So, now you have two symbols in a cause-effect relationship that obeys a particular formal system (in this case, the alphabet) and you probably feel pretty confident about what the next letter in the sequence is going to be:

You’d be wrong, though. Form doesn’t always follow expectation. In fact, the failure to follow expectation is actually one of the pleasurable aspects we get from narrative, and it’s only possible because we are able to read formal cues and make an assumption based on what we understand of formal structure. Now, we have to readjust our expectations – and we’ll have a new expectation now, too, which is that the sequence may well decide to pull the rug from under us, within an understandable and recognisable set of parameters. We can use this information to make a guess at what happens next.

Based on our understanding of the formal structure in play, we have two reasonable contenders for the next letter in the sequence: ABAB or ABAC. If you predicted the latter, you’re feeling pretty pleased with yourself and your engagement with the sequence has deepened. If you predicted ABAB, you were wrong-footed but not in an outrageous way, and that doesn’t stop you from continuing to make a hypothesis about the next letter, based on the established rules and your evolving understanding of how they operate in this game. So if we show you that the next letter is

that’s not out of line with what we understand the formal rules to be, and so it continues.

That’s not to say that it’s not a valid option for artwork to fail to satisfy expectation, to play with expectation, or to go out of its way to confound expectation. That’s perfectly valid, as long as the viewer understands that this is part of the formal structure. If you’re watching a murder mystery and it turns out, with no prior indication in the narrative, that aliens did it, you’re within your rights to go straight to Rotten Tomatoes and excoriate that mess. That kind of left-field shot was not part of the cause-effect relationship established by the narrative. Some narratives, though, actively go out of their way to disorient the viewer, and this is actively part of the satisfaction of engaging with that form of artwork.

Here’s a sequence from Un Chien Andalou, a surrealist short film directed by Luis Buñuel. That should set you up with some formal expectations right there – but just a warning for the squeamish; there’s a sequence very early in that’s just awful to watch. Just awful. You’ve been warned.

So, you can tell very quickly that your formal ABC expectation isn’t going to be of any use in this film. But that becomes your formal expectation. With a film like this – with any piece of artwork which deviates from a standard formal expectation – part of the satisfaction of viewing is also part of the challenge: one has to adjust one’s formal expectations to meet the film’s. You have to accept that you have no real framework for anticipating what comes next, and that in itself can be a source of consumer pleasure.

To quote from those film theoretical geniuses again:

“In recognising film form, then, the audience must be prepared to understand formal cues through knowledge of life and of other artworks.”

(Bordwell & Thompson, 1997, p71)

In the same way that you make assumptions about a film’s narrative according to what you understand about film form, and you make sense of a narrative according to your own experiences of life and your knowledge of narrative form, you also accept various elements of the filmic system in and of themselves as part of the order – the rules, if you like – of that film’s internal logic.

So, what does any of this have to do with montage? We’re glad you asked.

Continuity editing

Like we were saying, editing is, at its most basic form, the process of selecting and joining camera takes, but it’s also the process of making meaning from those selections and conjunctions. Now, we’re looking primarily at classical Hollywood style in this article series, and classical Hollywood style employs what’s known as continuity editing

Continuity editing emerged a little over 100 years ago as a very efficient way of maintaining continuous narrative action. How does it do that? By creating causal connections between shots. To understand what that looks like in practice, we need to go back to the first decade of the 20th century and say hello to a Soviet filmmaker called Lev Kulashov.

The Kuleshov Effect

Yep, you know you’ve made your mark on history when you have an actual effect named after you. And this one’s a doozy, too.

So, at the risk of labouring the point, continuity editing creates causal connections between shots. This happens because the human mind is uniquely and obsessively determined to make meaning between things that might not actually have any kind of actual connection. Lev Kuleshov, for his sins, found a way to demonstrate as much in 1910. It looks like this:

Okay, so, you kind of have to imagine this is happening on film and that each image appears singly and in sequence, otherwise it kind of loses a bit of its oomph, but this, in essence, is what Lev Kuleshov did to pass the time 110-odd years ago. The enigmatic looking chap is a noted film actor of the day. Kuleshov shot some footage of him looking enigmatic, and then intercut it with images of a plate of soup, a little girl in a coffin, and a woman on a divan. On playing the edited sequence to an audience, viewers were struck by the realism of Mr Enigmatic’s acting: how hungry he seems when he looks at the bowl of soup! What devastation he evokes upon seeing that poor little girl! Such lust in his eyes as he watches that comely young woman!

Except…

Yeah. No. He wasn’t looking at any of those things. It was literally the same bit of footage, repeatedly intercut. He was looking at the camera the whole time.

Editing and Causal Connection

It’s easy to get all twenty-first-century high-and-mighty about the naivety of early cinema audiences, but the fact is, you fall for the fundamental principles behind the Kuleshov Effect every time you watch a movie, friend. Have a little look at this…

If we ask you what you’ve just seen… well, clearly, you’d know we were up to something, because you’re clever like that, but, if pressed, you might roll your eyes and say something about Tippi Hedren and friends watching in horror as a guy – apparently lacking any sense of smell or self-preservation – accidentally sets himself and a gas station on fire.

You’d know, of course, that we were going to pull an “AHA!” on you, and you wouldn’t be even a little impressed when we did. So we won’t. We’ll just quietly point out that the Tippi-in-a-diner sequence was filmed on a soundstage in Hollywood while the Darwin-Award-contender sequence was filmed on location in north California. They’re not looking at a bird attack outside the window. There is no outside the window. What there is, is a big old expanse of studio, and maybe the art department trainee having his sandwich.

The point is, when there’s no physical connection between the contents of two separate sequences but our mind creates a causal connection – that’s the Kuleshov Effect in action.

Editing and Temporal Connection

Continuity editing can get us to make connections across time as well. Typically, continuity editing presents events in a 1-2-3 manner: a thing happens, this causes another thing to happen, which in turn causes another thing to happen, and so on. Alternatively, you can have a flashback, where a thing happens, and then we discover the historical reason for the thing happening, before we go back to the usual temporal progression. All well and good, and not really what we mean here.

What we mean is that continuity editing allows us to understand ellipses in the narrative — long periods in which much, much more time passes in the story world than passes for us. Kubrick’s (overrated – fight us) 2001 is a really famous example — to whit, the bit where the protohuman ape guy throws a bone in the air and it becomes a spacestation. That’s an ellipsis of literally tens of thousands of storyworld years, and yet we understand quite easily what’s happened. Tens of thousands of years have elapsed in the space of a split second. Has time travel been invented? Nope, it’s just a temporal ellipsis, brought to you by good old continuity editing.

There is, of course, another way to show the passage of time across several ostensibly unconnected shots — montage makes us connect them temporally. And in this case, we do mean “montage”…

Really, seriously, and in all honesty, you didn’t actually expect us to write an article about montage and not include that sequence, did you? Anyway, it was for science. That clip has more than justified its presence here by beautifully demonstrating, in glorious meta, how editing creates connections between disparate spatial locations and disparate temporal locations. There’s no reason at all to make those connections – except for the fact that your brain is trained to do this from years of watching films.

Again, none of this sprung fully formed out of the nascent art of moving pictures. All of this had to be learned – by both the encoders of meaning (the filmmakers) and the decoders (the audience). Early cinema did not know how to do this. Want some proof? Happy to oblige, but you need to watch to the end:

Did you notice how you just watched the exact same events take place twice in succession: once from inside the burning house, and then, immediately afterwards, from the vantage point of the rescuers outside? The director, Edwin S Porter, was an early innovator in the medium (and, in fact, one of the first to use continuity editing techniques), but when he made this movie there was no understanding, among filmmakers or film viewers, of how to intercut between continuous action in a way that created causal connections between the shots. He wanted to show both perspectives on the daring rescue. So he did. One after another.

Later that same year (1903), Porter made The Great Train Robbery, another classic of the early cinema, in which he does make an effort to show simultaneous action happening at multiple locations – through an early form of continuity editing, of course – so it wasn’t long before those first pioneers of the new technology began to actively play with the new film-linguistic possibilities. But the point is that, no matter how it might seem today, continuity editing isn’t a natural, or even obvious, phenomenon.

Before the visual language of film was developed, there was no instinctive understanding of things like cutting on action, or of editing for spatial or temporal continuity. You just presented a thing happening in one place, and then a thing happening in another place… and that was the extent of your editing. Job done. Goodnight.

And this is very much true of everything we’ve looked at over the past four posts.

Visual style: the heart, the soul and the the voice of film language

Because none of the meaning conveyed by elements of film language – not cinematography, not mise-en-scène, and not montage – is “natural” or “innate,” no matter how accustomed to it we’ve become. We have to learn to read it. Film is an incredibly powerful medium for communicating information, and part of that is because we are effectively being trained from our most formative years to understand the very subtle language it uses. When we talk about breaking down the language of film, we’re talking about changing from passive viewing to active viewing. We’re talking about becoming aware of the information flow as it’s being communicated to us. We’re talking about actively engaging with the film literacy that we’ve evolved so that we can look at the messages directly and decide what to do with the information communicated – and that’s a powerful skill to have.

CinePunked’s mission is to engage with film fans and audiences and use film to have the big discussions about the issues that matter. We believe that film literacy is an essential component of navigating twenty-first century life.

Film is ubiquitous. It’s everywhere. And, where it’s trying to strike up a conversation between the maker and the audience, we should all be able to join in.